Having just attended RootsTech 2017, I feel compelled to

compare the state of genealogy with my previous observations and viewpoints, as

reported last year in Evolution

and Genealogy. What has changed, and in which direction? I will also make

some concrete suggestions to the industry that could go a long way to averting

the headlong demise of online genealogy.

Figure 1 – Compost frenzy.

This year’s Innovator Showdown semi-finalists presented

products with the following functionality: photograph/image tagging and

organisation, indexing, DNA triangulation, transcription, stories and memories,

celebrity/friend tree matching, and newspaper research. That’s quite a broad

range, and by itself doesn’t give away much in terms of trending. Some of the

products were specialised, but others offered insular functionality, divorced

from complementary functionality elsewhere — a point that I also mentioned last

year. You would be forgiven for asking why

can’t I have that, together with that, and inside this?

The overall message of RootsTech was still about stories and

memories, and I’m totally on-board with this, but it is just the tip of a

bigger requirement involving narrative. I applaud any change of focus away from

raw data on trees to descriptive and audiovisual media that real people can

relate to — allegedly allowing us to become heart

specialists — but narrative (as favoured by humans but not by software

designers) has many critical uses that were not addressed at the conference.

More on this in a moment.

On the Wednesday (Feb. 8th), there was a session

entitled “Industry Trends and Outlooks” with a panel that included Ben Bennett,

Executive Vice President of International Business at Findmypast, and Craig Bott, co-founder, President

and CEO of Grow Utah. Their particular comments were enlightening about current thinking

in the commercial sector.

Ben acknowledged that not everyone wants to

build a tree (or at least not just a tree), and that companies needed to

understand their “customer context”. He was making the point that there is a

mass market — apparently 83M people in the US interested and willing to pay —

that involves a broad range of skills and interests, so how do you engage it.

He suggested that products needed differentiation, with functionality aimed at

the requirements of their particular customer group. I’m sceptical of this

suggestion since it could be interpreted as different skills and depth of work

translating into functional differences rather than user-interface (UI) ones;

does the fact that some people write or research better than others necessarily

mean that they’re the only ones wanting to do it?

Ben also acknowledged that good ideas don’t

just come from within companies, and that they [Findmypast] are looking externally and willing to talk about new

innovation. I believe this meant demonstrable products rather than written

ideas, but it’s probably as close as we can expect to outreach so I wholly welcome his comments.

Craig talked about new technology in the

areas of OCR

and handwriting recognition — functionality that we all want — but also went on

to describe neural

networks being applied to the identification of named entities and semantic

links. What this means is being able to pick out personal names, places, dates,

events, etc., from digitised text, and also the relationships between them:

biological or social relationships between people, origin or residence of

someone, and dates of vital and non-vital events. Well, I have to repeat something

that I’ve said elsewhere: it’s people that perform genealogical research, not

software. Highlighting named entities could be an aid to newspaper research,

but the researcher would be analysing the text, and across multiple documents

rather than just one at a time.

My take on all this is that the large

companies feel obligated to throw technology at genealogical (and historical)

research, but the more fundamental issues of real research are not being

addressed, or even acknowledged.

I make no secret of the fact that I dislike

online family trees as they’re currently implemented. They do not capture

history, they make it far too easy to connect the wrong dots, and they’re an

inappropriate organisational structure (i.e. they should be simply a

visualisation of lineage). I’ve justified these points in previous posts, but

let me summarise some of their basic failings that really need tackling.

a) They are person-centric when it is time to enter data. For instance,

in order to enter all the people in a given census household, it is nearly

always necessary to start with each person in the tree, and then add each

so-called “fact” and associated source to them. This is quite laborious as you

really want to work from the census household rather than from the tree, and you

have to frequently re-consult and re-describe the same document. If you want to

attach an image of some document, say because you have a paper copy that’s not

online at the current host site, then you’ll also be forced to attach it

multiple times (hopefully not independent copies).

b) When a source is added to a “fact” then it is a direct connection with

nothing in between: no analytical commentary; no transcription; no

justification for why it’s appropriate to the selected person; and no

explanation as to why the name might be slightly different, or the

date-of-birth implied by an age slightly different, from your conclusions. A

consequence of this is that there’s no way to determine how a given conclusion

was reached by someone.

c) There’s no obvious way to add material that relates to multiple

people. Photographs and document images are obvious examples, but the same

problem relates to stories/memories, transcriptions, and any researched

histories of your ancestors.

d) There’s no obvious concept of ownership in a unified family tree. While

still controversial in some quarters, most users do want this. As I

mentioned last year, certain contributions should be immutable, but which?

While a mere collection of “facts” can have no ownership (and cannot be

copyrighted either), authored works such as research articles and personal

memories must have.

e) There will always be multiple possible conclusions in unified trees; anyone

disputing that needs to understand the concept of evidence better. If there are

no controls then there will be edit wars,

and potentially loss of valuable contributions, but what form should they take?

Throwing complicated technology at this in order to support multiple versions

of the “truth” isn’t necessarily the right solution, and we need to take a step

back and look at the dynamics of real research. Consider: what we’re doing isn’t always what we think we’re doing.

f) Copying is made too easy in online trees, either from someone else’s

tree or from material found elsewhere. In an ideal world then it should not be

necessary, but these trees offer no alternatives. Their lack of functionality

may even force users to put certain material elsewhere, thus leading to other

users feeling they have to copy rather than cite or link-to it. This all means

that errors, or even tentative conclusions when a researcher hasn’t yet finished,

will replicate like a virus. It also means that the provenance of a

contribution is lost, and there can be no attribution to the original author, contributor,

or owner.

While I dislike trees,[1] I do acknowledge the investment that sites may have in that paradigm.

So what can be done to address these failings, and help trees evolve to meet

more of the requirements of that mass market?

The scheme I want to suggest to companies

that host online family trees involves using separate layers. Back in Our

Days of Future Passed — Part III, I explained how the STEMMA data model has

two notional sub-models: conclusional

and informational. The old GenTech

data model also had separate sub-models, although its equivalent to informational was termed evidence. STEMMA purposely uses the term

informational as its sub-model

includes the information sources and the possible analysis of that information,

irrespective of whether it contributes evidence relevant to some conclusion.

When information is cleanly separated from

conclusions then it provides a natural distinction for controlling changes to

the corresponding contributions.

Conclusions — which includes names, dates, and relationships in the online

tree — would be editable by anyone, whereas information — which includes

personal stories and memories, photographs and images of documents, source

analysis, research, and proof arguments — would be editable only by the

respective contributor (or possibly some registered agent, such as another

family member).

Figure 2 – Conclusional and informational layers.

If someone had uploaded a photograph then a person in the

tree could be linked to it, and although the link might be changed by anyone,

the photograph could not. Similarly, if someone had uploaded their written

research then conclusions on the tree could link to its relevant parts, and

although those links could be changed by anyone, the original article could

not.

I’ll expand on how this would work later, but first I want

to point out an important subtlety: the arrows in this diagram are shown as

down-pointing, from the conclusions to the associated information (including

evidence). This would not be visible to the end-user since a connection is

simply that (with no direction), but it is important for the purposes of change-control.

If the source of the link was in the conclusional layer then it could be edited

by all, but if it was in the informational layer (i.e. up-pointing) then it would

be classified as part of the information source, just as we treat opinions in

an authored work.

This may sound as though it offers redundancy rather than

flexibility, but the distinction will become clearer as I progress.

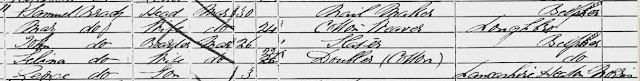

The following example is from the 1861 census

of England and Wales (Piece: 2560, Folio: 23, Page: 6), and represents the

household of 8 Homleys Court, Heaton Norris, Stockport, Cheshire. It was used

as an example

on the STEMMA site because it contained a number of errors, errors that had

to be explained before identification of the persons could be made. The family

name was incorrect, relationships were ambiguous, ages were wrong, and place

names were wrong. Simply connecting “facts” on a tree to this census page would

be silly as there would be so many discrepancies.

|

Name

|

Relation

|

Condition

|

Sex

|

Age

|

Birth Year

|

Occupation

|

Birth Place

|

|

Samuel Bradley

|

Head

|

Married

|

M

|

30

|

1831

|

Nail Maker

|

Belper, Derbyshire

|

|

Mary Bradley

|

Wife

|

Married

|

F

|

24

|

1837

|

Cotton Weaver

|

Lougborough, Leicestershire

|

|

John Bradley

|

Boarder

|

Married

|

M

|

26

|

1835

|

Slater

|

Belper, Derbyshire

|

|

Selina Bradley

|

Boarder’s Wife

|

Married

|

F

|

22

|

1839

|

Doubler (Cotton)

|

Belper, Derbyshire

|

|

George Bradley

|

Boarder’s Son

|

-

|

M

|

3

|

1858

|

-

|

Heaton Norris, Lancashire

|

Table 1 – 1861: Household of Samuel

Bradley. Extracted and corrected details.

Figure 3 – 1861: Household of Samuel Bradley. Cropped image.

For a user-owned tree, using the

informational layer provides the currently missing place to extract the details

and to explain why they might be incorrect. This alone would prevent users

trying to create multiple birth events when sources disagree, but it would also

provide them with a chain of explanation that they could follow at a later

time.

It would also allow the user to work with,

and from, a document in a source-based manner, thus making their data entry

more efficient. Any analytical commentary and citation (should one be needed) would

be in one place that could be linked to all the relevant tree entries.

In a unified tree, adding a copy of an image

(or a hyperlink to an online version) only need be done once, but the

extraction of details and the associated analysis might be done by different

people. In other words, there could be multiple contributions that don’t exactly

agree. This is in the nature of research and it must be accommodated.

The case of a document transcription is

analogous since one version may be more precise than another, or may have

interpreted hard-to-read text differently, or may have added annotation

clarifying some aspects.

Authored works, including personal

stories/memories and research articles, are crucial for capturing history. The

mere inclusion of these would provide additional source material that could make

the overall experience in online trees much richer. Research material willingly

shared by those who make that effort would also serve to help those who can’t

or won’t. Currently, anyone wanting to share such material has to use a separate

blog (as I do) or some personal Web site; simply dumping your work in a

plain-text area, with no formatting, no tables, no pictures, and probably

attached to a specific point in some tree, just doesn’t cut it in the real

world.

This scheme would make it much easier to

accommodate material that relates to multiple persons since it is not hung

directly from any one tree branch.

A point I hinted at earlier is that the

author of such works is making connections — opinions — that identify the

persons referenced in various sources. Taking one of my articles as an example

(Jesson

Lesson), this makes a case for various family relationships and their vital

events. So how would this get connected to a unified tree; how would my up-pointing

opinions relate to the down-pointing conclusions on the tree?

Well, remember that what we’re doing isn’t always what we think we’re doing. The

researcher will have put together the details and relationships of a small

group of people, but they haven’t slotted them into any global tree; that’s

manifested in the conclusional layer. Also, their opinions may differ from

those of another researcher and so the final conclusions must arbitrate based

on their narrative explanations.

STEMMA would rely on semantic tagging (i.e.

mark-up) embedded within the text to identify individual references, but that

would be too complicated for most online trees. Imagine, instead, that each work

was annotated with a piece of structured meta-data[2] that enumerated the (possibly multiple) names of the referenced

people, their relationships, and their vital events. This would represent the

opinions of the author and so would be an immutable part of each work —

effectively up-pointing connections, although we won’t use them like that.

The meta-data would be cataloguing the works

as complete units rather than their individual references but there are some

advantages to that. In fact, this is the same meta-data concept that I

described in Blogs

as Genealogical Sources, and so it would also cope when the authored work

is published elsewhere, including blogs and even traditional books.

Figure 4 – Meta-data for local and remote articles.

That article about using blogs as sources made

the point that this meta-data should be created by the respective author — not

by some neural net software trying to second-guess them — and that it could

support even the most complex of genealogical searches that these sites have.

In this scheme, it summarises the details that the article has found or derived in its

narrative.

Maybe surprisingly, when a humble photograph

is added to the informational layer then the situation is analogous to that of these

authored works: the contributor may have identified the people present in the

shot, but we all know that old photographs often get mislabelled. How nice,

though, to be aware of who made the identifications, and how. If two people

have differing information for the same image then we can arbitrate using their

explanations.

Having source information, source analysis,

and even authored works, in the informational layer would provide a rich substrate

to feed the tree-based conclusions. Edit wars and accidental loss of data are avoided

because the main user contributions are in the informational layer. But there

will still be differences of opinion since nothing is certain when looking at

past events. In this scheme those alternatives could co-exist with virtually no

effort, but which do the conclusions point to?

What the scheme affords is the ability to

arbitrate on the quality of some research, or other contribution, and not simply

on the preponderance of conclusional instances.[3]

I now want to extrapolate to see how far it

might be possible take this scheme. Back in What

to Share, and How - Part II, I presented a diagram explaining about joining

STEMMA contributions together to automatically form a tree. Well, the same

principle could be achieved using the contributions in this informational layer

when they have the appropriate meta-data attached, as described above. In other

words, if all the contributions were in unanimous agreement then construction

of the tree could be automated.

But what about when they disagree, as is the

normal case? This was a concern that I had in the aforementioned article, but when

compared with the current situation of disagreeing contributions, these would

be backed up by material whose quality could be used for arbitration. Not only

that, this arbitration could be achieved using the ubiquitous Like button, stressing again that those

differing opinions would all still be available, and nothing would be lost or

discarded.

I hasten to add, here, that any

implementation should avoid the temptation to use the researcher’s reputation,

whether based on their ‘likes’ or their external persona. When a name is

recognised then it might be tempting to ‘like’ their research without actually reading

it. I know through experience[4] that an amateur who is driven to solve a mystery that’s very close to

them, without the constraints of time and money, can make a better job than a

qualified professional.

This may be a step too far in evolving shared

trees since it would mean a quite different way of working for users. But the

use of a Like button can still be

employed to rate contributions in the informational layer.

This categorisation and separation of data

contributions is something I already do in STEMMA; however, as I’ve presented

here, it does not mandate the STEMMA data model. In fact STEMMA’s very broad

micro-history scope would be (currently) inappropriate for those sites hosting

family trees. What I’ve done, here, is to explain the principles in terms that

apply to online trees. FamilySearch

are quite close to this already since they have a separate memories area with

different change-controls. The connections between this area and their unified

tree would need work, and their narrative contributions would need some form of

mark-up (not just plain ASCII text), but these are doable. Rather more effort

would be required to handle the analysis and extraction facilities for

source-based input.

So what’s different here? Isn’t this an

obvious approach? Maybe it is in retrospect, after reading this article.

Fundamentally, it breaks with the traditional notion of a tree as the organising

structure within the software. If the industry can move beyond that then it

would help with engaging that mass market and its many requirements — ones that

I believe are actually common to us all, but maybe to different depths.

For me, personally, it’s not just about a

revenue stream; it’s about giving users what they really need, it’s about the

reputation of genealogy as a pursuit, and it’s about leaving a valuable legacy

for future generations.

[1] I am

interested in lineage, but also family history and micro-history; a tree merely

visualises that lineage, and is inappropriate for organising any type of

history.

[2] Structured usually means XML these days, and that’s good for handling user

maintenance operations. If they are going to be searched or manipulated in bulk

then a database derivative will probably be required.

[3] I use this term

deliberately since there are generally few independent conclusions, but many

replicated instances of those same conclusions.

[4] My entry into

genealogy involved solving a family mystery, and hence fulfilling a promise

that I made to my mother. I was told, by a professional, that it was

impossible; it took me several years but I succeeded and so changed a number of

lives forever.