This question should be of interest to anyone who has considered publishing their family tree on a subscription-free website that requires nothing extra to be installed.

Maybe you haven't thought about this in any great depth, but the website or desktop product that you currently use to maintain your tree is going to be inappropriate for some of your family and friends. Assuming that you do want to share with them, they will simply want to link to some web page, without paying for anything or having to install anything, and see a presentation edition of your tree, your family history, your images, etc. They won't want to see any buttons or options for maintaining that information.

This was the situation with all but two of my extended family wanting to see my own research (those two also happened to be genealogists), and so I decided to develop some software with this goal in mind. I also had a goal of drawing trees that could be included into my blog-posts so I came up with a tool that satisfied both requirements: SVG Family-Tree Generator (SVG-FTG). But what is this SVG?

SVG stands for Scalable Vector Graphics. It is a language for defining graphical shapes in your browser, and handling user interaction with them. It is quite different to normal image formats as it scales indefinitely without going fuzzy when you zoom in. SVG-FTG converts your family tree, including biographical notes and images, into an HTML document that employs SVG to produce the graphical parts of your tree, CSS to style the presentation, and JavaScript to handle user interaction.

Figure 1, a common example of what SVG can create.

I will try not to get too technical, but I do need to make some clear and careful points as SVG often gets "bad press" for inappropriate reasons. SVG is like a sister technology to HTML: HTML is good at presenting text, forms, menus, images, and frames around such content. It's ubiquitous so I don't need to describe its full capabilities; SVG is good at drawing shapes and lines, and including text or images within those shapes.

Superficially, their structure looks the same with their elements defined by opening and closing tags, each in angle brackets. For instance, this small HTML extract presents a level-1 heading with a paragraph of text following it:

<h1>This is a title</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph

of text</p>

The following SVG extract draws a rectangle with a circle inside it:

<rect x="100" y="100" width="200" height="200" fill="yellow" stroke="black" stroke-width="3"></rect>

<circle cx="200" cy="200" r="90" fill="orange" stroke="navy" stroke-width="10"></circle>

SVG is technically a separate XML-based language, which means that its syntax follows slightly different rules to HTML, but that difference is not relevant here. It does mean, though, that it can be placed in specific files of its own — usually named *.svg — and they can be treated like normal image files, but more on this in a moment.

When the SVG is embedded within an HTML document then it is referred to as "inline SVG", and this is what SVG-FTG generates in order to produce a graphical user interface (UI). Together, these two contributions to the UI — HTML elements and SVG elements — can produce a very sophisticated presentation. They also share the event mechanism, which basically means that the way they respond to user clicks and button presses is the same, and that means that they collaborate to implement an application: a tool delivering useful functionality to the end-user.

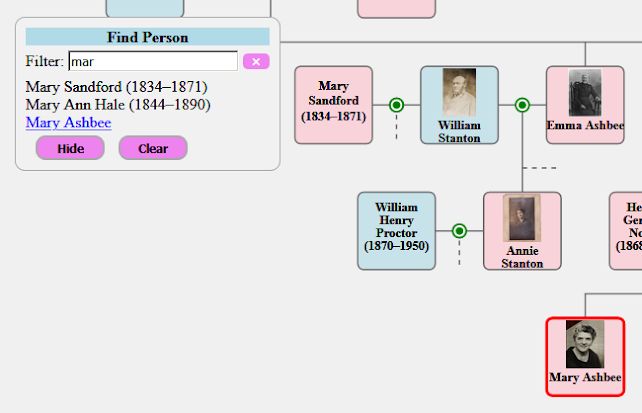

Figure 2, Example of application generated by SVG-FTG.

So, in this guise, there is nothing sinister or risky with SVG; it is simply another contribution to the UI. It uses JavaScript and CSS in the same way as most HTML pages do.

But the other scenario — that of separate SVG files — is subtly different. They're really document files rather than image files and so can also contain JavaScript and CSS. The problem comes if they are naively treated as image files because they can harbour malicious content. For instance, if they are deployed as a CSS background image, or a logo on some website, or in some image gallery then such content could be activated. At the very least, this could lock-up your browser (the so-called 'Billion Laughs' attack), but could also lead to 'HTML Injection' and 'Cross-Site Scripting' attacks.

This means that many sites capable of loading images are very careful to either disable such SVG image files or sanitise them by removing any script. Unfortunately, this protective action can spill over into a complete rejection of SVG because the two scenarios that we've mentioned have not been sufficiently well defined and distinguished.

One example of this involves Wordpress.com — not Wordpress.org which is the self-hosted and unrestricted variant. It is well known that you have to jump through hoops to get any <script> or <style> elements into your page, as well as certain special ones such as <embed> and <object>; but it also seemed to strip out inline <svg> elements for no apparent reason. Note that the <svg> element is not mentioned at all on their page: https://wordpress.com/support/code/ (at the time of writing), leaving its viability in some doubt.

There are various plug-ins that may be used with Wordpress.com but all of the ones that I am aware of relate to the loading or sanitising of "SVG files", which we explained is not our situation.

When pressed on this point, and given the specific example of the TimelineExample.html mentioned in the SVG-FTG guides, their support provided the following details.

Users would most likely need to upload the above mentioned HTML file through SFTP and not including it between the custom code widget/block. They’d also need to be upgraded to at least the Business plan to be able to do that. [13 Apr 2021]

When specifically asked about support for the <svg> tag, the following response was given:

By default SVGs are something that’s not allowed/supported by WordPress, so I guess they’d need to install a third-party plugin that allows them to be able to work with and include SVGs... [13 Apr 2021]

The term "SVGs", used here, would appear to mean "SVG files", which I went to great pains to eliminate as not relevant to my question. It does seem as though they are fixated on "SVG image files" and have little concept of its usage to provide a graphical UI for an application.

However, after escalating this issue, Wordpress.com demonstrated to me that it is actually possible to host these SVG-FTG applications on their site under the Business Plan, and that the process is not too different from the Wordpress.org one. In their words: “It is also a simple process of copy and pasting. Although, I added all the CSS and JS to the head of the site as on your example URL and only loaded the content in the body via the Custom HTML block”. Hence, although neither of these Wordpress scenarios is actually free, it is possible to host SVG-FTG applications on them both. It’s just a shame that “inline SVG” is so poorly understood and catered for, generally.

For a successful alternative, see this videon Publishing your tree for free with no hassle.