Not many of us will have found an ancestor who had fallen

victim to a case of copyright infringement, but fewer still will have found an

ancestor who was involved in an important copyright case — one that is still

cited in modern textbooks because of its unusual circumstances.

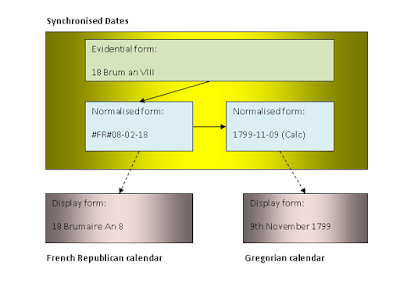

Figure 1 - The trap for the unwary looking for gain.

According to various census returns, William Ashbee was born

c1803 in Hillesley, Gloucestershire, but he was baptised about 2.5 miles south

of there at Hawkesbury, on 6 Mar 1803, to Isaac and Hester Ashbee.[1]

Following the reading of the Banns on 18 Jun 1825, he married Ann Hayward in

the parish of Westonbirt, about 7 miles east of Hillesley.[2]

In 1841, they were living in Fox Hill, Tetbury, about 13

miles E-NE of Hillesley, and William was a ‘mason’[3],

apparently the same as his father. By this time, they had established their

family of four children whose ages then ranged from 4 to 15.

Figure 2 - Family Tree of William and Ann Ashbee.

In 1851, they were still living in Fox Hill but William was

now a ‘baker’.[4]

Interestingly, the next household on that census page — actually on Silver

Street — was of the Godwin family; the family into which William’s eldest son,

Thomas, would wed later that year.

In 1861, they had moved to Long Street, Tetbury, and William

was now a ‘baker & grocer’.[5]

Also in the household was their 8-year-old granddaughter, Jane A[ugusta]

Ashbee. She had been born to Thomas Ashbee and Sarah Jane Godwin on 25 Sep 1852[6],

but her mother had died either during or shortly after the birth. I can find no

record of her death but Thomas remarried to Eliza Dean in 1854.

In order to further establish the occupation and location of

William during these years, I consulted a number of trade directories, and

these yielded the following information:

|

Date

|

Location

|

Occupation

|

Notes

|

|

1849

|

The Green, Tetbury

|

Baker

|

[a]

|

|

1852–53

|

Long St, Tetbury

|

Baker

|

Proprietor was a Mary rather than William.[b]

|

|

1856

|

Long St, Tetbury

|

Baker & Grocer

|

Mrs Mary Ashbee is also a baker at Gumstool Hill.[c]

|

|

1868

|

Silver St, Tetbury

|

Baker

|

[d]

|

[a] Hunt & Co's Directory of Gloucester & Bristol, 1849, p.172

(image 175 of 587), online PDF, University of Leicester, compiler, Historical Directories

(http://specialcollections.le.ac.uk/ : accessed 8 Feb 2015).

[b] Slater's Directory of Berks, Corn, Devon, ... Glos, ..., 1852-53,

p.162 (image 564 of 1070), Historical

Directories.

[c] Post Office Directory of Gloucestershire, Bath & Bristol, 1856,

p.369 (image 380 of 619), Historical

Directories.

[d] Slater's Directory of Glos, Herefs, Mon, Shrops & Wales, 1868,

p.271 (image 283 of 1151), Historical

Directories.

What this information shows is that William was still

associated with baking in Tetbury, right up until 1868. This is important

because he changed his profession to that of publisher around this same time,

and he obviously took the decision quite late in life as he was nearly 65 years

old.

Figure 3 - Long Street, Tetbury, 1949. © The Francis

Frith Collection.[7]

William Ashbee, in partnership with Louis (or Lewis)

Simonson, Edward Dutton, and Francis Alexander Lamb, formed a new publishing

company called Ashbee & Co.

However, their first work, The Merchants’

and Manufacturers’ Pocket Directory of London, immediately ran into trouble:

an injunction on its publication and sale was sought by John Stuart Crosbie

Morris, publisher of 4 Moorgate Street Buildings, on the grounds that it was

pirated from his own Business Directory

of London. I cannot determine when the bill was filed but the law suit —

more formally known as: Morris v. Ashbee

(1868) LR [Law Report] 7, Eq. [Equity case] 34 — was already partially heard by

4 Nov 1868.[8]

The bill alleged that the four defendants (identified above)

had been previously employed by Morris (the plaintiff) as canvassers in the

preparation of his own directory, published in 1867. Morris suspected that

Simonson was going to bring out a directory of his own, in opposition to his,

and so he was fired. Morris wanted the other three to sign an undertaking that

they wouldn’t join Simonson unless they were discharged from his service, but

they refused and so they were fired too. The four defendants were reported to

have commenced business at 190 Gray’s Inn Road and had published their own directory

in January 1868.[9]

An advertisement for canvassers was running during December

1867 that was using this address and so it further refines the date at which Ashbee & Co. began operating:

“Ten respectable men wanted, to

canvass for orders for a new copyright engraving. Directory canvassers

preferred. Apply, personally, until 17th inst., between the hours of 10 and 2,

at 42 Charlotte-street, Portland-place, W.; or between 3 and 7 O'clock, at

Ashbee and Co.'s, 190 Gray's-inn-road, W.C. canvassers now realizing between

15s and 20s per day”.[10]

By the time the bill was served, Ashbee & Co. were operating from 32 Bouverie Street, off Fleet

Street, London. These premises had, for some time, been associated with another

publisher called Thomas Murby, known for his “Excelsior Reading Books” and “Indestructible

Binding for School Books”.

Figure 4 - Fleet Street, London, c1886. © The Francis

Frith Collection.[11]

Morris claimed that defendants had pirated information from

his own directory, and some cases of typographic errors having been duplicated

were used to substantiate this allegation. However, the court was satisfied

that wholesale copying had not occurred.

The defendants admitted that they cut-up the plaintiff’s

directory and pasted strips onto new sheets, but claimed that these were merely

used by their canvassers to locate prospective clients for their own directory,

and that the form and layout or their directory was wholly their own. This is

where the detail of the case gets very murky since Morris was the defendant in

a previous case: Kelly v.

Morris (1866) LR 1 Eq. 697. Frederic Festus Kelly’s Post Office London

Directory was used in a similar way by Morris to direct his canvassers as opposed to actually copying any of the

source material. There were also more serious allegations of pirating involved in

that case as many typographic and other errors, and details of deceased persons

and defunct businesses, had crept into the newer directory. Morris lost that

case and an injunction was served on the associated directory: The Imperial Directory of London.

The main difference in Ashbee’s case concerned the fact that

advertisements were public property. Morris still used a similar technique that

collated information from public advertisements, newspapers, flyers, etc., as

well as previous editions of his own directory, in the preparation of material

to direct his canvassers. Ashbee claimed that since trades people paid Morris

for additional differentiators — such as their names appearing in capitals, or

“extra lines” describing their business, or actual advertisements near to their

directory entries — then those specific entries amounted to advertisements and that

he was entitled to use them in a similar way to Morris.[12]

In fact, in Simonson’s evidence, he claimed that on leaving

the employment of Morris, in April 1867, that he had told him not only of his

intention to create a pocket directory, but also the manner in which he was

going to use a copy of his directory, but Morris allegedly made no complaint.[13]

Although the Morris v.

Ashbee case had some differences from the prior Kelly v. Morris case, there were still strong similarities: namely

the contention that a mercantile directory was intended to be used in order to

locate trades people and their addresses, and that entries were deliberately

arranged in alphabetical order of name and of trade to facilitate this. This

might be obvious in any context except one involving the production of a rival

publication.

So what do you think? Was Ashbee in the wrong, and if so

then in what way? In the follow-up to this article, I will discuss the details

of how the case went and what the repercussions were.

[1] "England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975", database, FamilySearch

(https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NP5Y-3MQ : accessed 24 August 2015),

William Ashbee, 6 Mar 1803; citing HAWKESBURY,GLOUCESTER,ENGLAND; FHL microfilm

425,436, 856,929.

[2] “Marriage Banns”,

database, TheGenealogist (http://www.thegenealogist.co.uk

: accessed 20 Feb 2015), entry for William Ashbee and Ann Hayward, 1825,

Westonbirt parish.

[3] "1841 England Census", database with images, Ancestry

(www.ancestry.co.uk : accessed 24 Aug 2015), household of William

Ashbee (age 38); citing

HO 107/362, book 11, folio 39, page 13; The National Archives of the UK (TNA).

[4] "1851 England Census", database with images,

Ancestry (www.ancestry.co.uk : accessed 24 Aug 2015), household of William Ashbee (age 48); citing HO 107/1967, folio 176, page 19; TNA.

[5] "1861 England Census", database with images,

Ancestry (www.ancestry.co.uk : accessed 24 Aug 2015), household of William Ashbee (age 58); citing RG

9/1780, folio 44, page 36; TNA.

[6] England, birth certificate for Jane

Augusta Ashbee, born 25 Sep 1852; citing 6a/296/380, registered Cirencester 1852/Dec [Q4]; General Register Office (GRO), Southport.

[7] Long Street, Tetbury,

1949. Image © The Francis Frith Collection, ref: T155019 (http://www.francisfrith.com/us/tetbury/tetbury-long-street-1949_t155019

: accessed 27 Aug 2015). The hotel visible on the left is the Ormond’s Head

Hotel (no. 42), which was in the 1861 census and is still there today.

According to UK Pub History, this

apparently had some connection with the Ashbee family at a much earlier date (http://pubshistory.com/Gloucestershire/Tetbury/OrmondsHeadTavern.shtml

: accessed 26 Aug 2015).

[8] "Law Intelligence: Court of Chancery Nov.4: Morris v.

Ashbee", London Evening Standard

(5 Nov 1868): p.7, col.1

[9] "Law Intelligence: Equity Courts - Tuesday: Morris v.

Ashbee", Morning Post (11 Nov

1868): p.7, col.3.

[11] London, Ludgate Hill

From Fleet Street c.1886. Image © The Francis Frith Collection, ref: L130184 (http://www.francisfrith.com/us/london/london-ludgate-hill-from-fleet-street-c1886_l130184

: accessed 27 Aug 2015).

[13] "V. C. Gifford's Court: Morris v. Ashbee and Another", The Law Times Reports; Containing All the Cases Argued and

Determined in the House of Lords, the Privy Council, the Court of Appeal ..., Volume XIX [19], September 1868 to February 1869 (London: Horace

Cox, Strand, 1869): pp.550–3.