In A

Calendar for Your Date — Part I, I mentioned the changeover from the Julian

calendar to the Gregorian calendar. People who have read about this may have

heard terms such as dual dates, double dates, double years, new/old style,

but do you really know what they mean? Was the handling of this changeover a

special case — one that needs its own treatment in our data — or was it really

an example of a generalised case? It’s time to take the lid off.

Figure 1 - Synchronised swimming in a sea of dates.

The Gregorian calendar was introduced by papal bull on Thursday

4 Oct 1582, Julian (followed by Friday 15 Oct 1582, Gregorian), but a couple of

factors prevented its automatic adoption everywhere. One of these was the fact

that it was devised by the Roman Catholic Church, and so in a time of

especially fraught church tensions other churches saw it as some type of power-play

and resisted. For instance, although other Catholic countries in Europe adopted

it either immediately (e.g. Spain), or later that year (e.g. France), or the

following year (e.g. Netherlands), Britain, including its colonies — some to

later become part of the US — didn’t change until Wednesday 2 Sep 1752, Julian

(followed by Thursday 14 Sep 1752, Gregorian; the difference by that time being

11 days rather than 10). Another factor was that many people considered that

days were being stolen from them — between 10 and 13 days, depending on the

date that their changeover occurred. Birthdays and anniversaries changed,

events changed, and that shortened year (282 days for Britain) created

difficulties for handling taxes, deadlines, and interest.[1] So

why were days taken away?

To understand this, it is important to know the reasons for

the calendar change. The length of the Julian year was too long (365.25 days)

and that meant that the Easter date was drifting backwards from the traditional

date as defined by the early church. There were therefore two main parts to the

calendar change: the solar part whereby new leap-year rules corrected the

average year to 365.2425 (much closer to the measured average of 365.24219

days), and the lunar part which corrected the cumulative error of 13 centuries

of drift by removing 10 days.

To complicate things slightly more, the British year was

also deemed to start on the 1st January rather than the 25th

March (Lady

Day) that it had done since the 12th Century (except in Scotland

where they had already changed in 1600). The UK Calendar (New Style) Act 1750,

which introduced the calendar changeover, justified the adjustment of the civil

year by “Whereas the legal supputation of the year of our Lord in England,

according to which the year beginneth on the twenty-fifth day of March, hath

been found by experience to be attended with divers inconveniences, not only as

it differs from the usage of neighbouring nations, but also from the legal

method of computation in Scotland, and from the common usage throughout the

whole kingdom, …”.[2] Note

that 1st January had long been celebrated as the start of the

“historical year” (New Year’s Day) but the Gregorian calendar was essentially a

civil calendar, and this was part of the reason why the church could not

mandate it. The terms Old Style (O.S.)

and New Style (N.S.) are often used

to clarify the ambiguities of dates falling between 1st January and

24th March. Old Style meant

that something was dated according to the old civil year and so must be

adjusted to align with the New Style

civil year, or to the historical year.[3]

The fact that the civil and historical years were already

different in Britain, even before the calendar changeover (except in Scotland),

meant that there was already a means of representing a year combination using a

notation informally called double years.

For instance, 3rd March 1733/4 clarified that this was March of the

civil year 1733 and of the historical year 1734 (i.e. the month before April

1734). Following the Julian-to-Gregorian

calendar change, the difference of 11 days meant that it was not just the year

that was different; a date such as 10/22 January 1705/6 explicitly represented

both the Julian and Gregorian dates, including their corresponding years.[4]

This was another form of a dual

date, or double date although

this term is no longer preferred due to the ambiguity with the social occasion of the same

name.

Even today, the start of the old civil year affects everyday

life in Britain since the start of the personal tax year remained at 25th

March (O.S.), or 5th April (N.S.), until 1800 when it moved to 6th

April. Britain also retains a double-year

notation to indicate that a tax year spans two year numbers, e.g. 2011/12.

Although Easter should fall on the Sunday following the full

moon that follows the northern spring equinox, both the full moon and the

equinox are now determined by calendar rules rather than direct observation.

This means that the date calculation (Computus) now differs in

different calendars, in different localities, and in different religions. Not

all holy festival dates were moved during the changeover, though; the date of

Christmas was already 25th December in the Julian calendar. This was

subsequently retained by all Western churches, and by some Eastern ones. The

equivalent Julian date (in this present time) would be 7th January,

and some churches do continue to use that date.

A large part of the confusion must be attributed to the fact

that the same calendar era was used — meaning that year numbering was designed

to run, as consecutively as possible, from the previous ones — and that the

same month names and day counts were retained. Hence, when birthdays or

anniversaries had been “bumped up”, it appeared to be a seriously intrusive

change, despite the measurement actually being according to a different

calendar scale. It is interesting to observe that this demonstrates how

indispensable the notion of a calendar had become, and how people attached

greater significance to the day number and month name than to the actual time

of the year.

If the change had merely included new leap-year rules then

no one would have noticed until the next difference (year 1700). Even the

change of the year start would have been manageable since countries such as

Scotland had already achieved it. However, the correction of 10 days, combined

with retention of the old months, appeared as though days were being stolen,

and it supposedly caused riots. Finally, the pope’s bull came at a very

difficult time as far as relations between the Catholic and Protestant churches

were concerned. It was issued in the reign of Elizabeth I and in 1584 a

previous attempt was made to adopt it. An act was prepared entitled ‘An act to

give Her Majesty authority to alter and make a new calendar, according to the

calendar used in other countries’. Although the bill passed two readings in the

House of Lords, stalling tactics by Protestant bishops ensured that it was

eventually ignored.[5]

When we observe dual

dates written during this chaotic transition, or from the period before,

when the civil and historical years differed, we can identify two dates

expressed according to distinct calendars: the Julian and Gregorian, or Julian

with civil and historical years, respectively. In other words, it was not

always the case that dual dates

represented Julian and Gregorian dates during the changeover — a common

misconception. What the cases have in common is that the date pairs represented

the same day.

In A

Calendar for Your Date — Part II, I made a case for holding an additional

normalised (computer-readable) version of our dates, but how should this be

extended to such pairs? The situation is not a special case as there are other

precedents for representing the same day according to different calendars. In

Israel, for instance, government documents usually carry a dual date embracing both the traditional Hebrew calendar and the

Gregorian calendar. Similarly, following the calendar reforms of India, in

1957, government documents carry a dual

date embracing the new national calendar of India and the Gregorian

calendar.

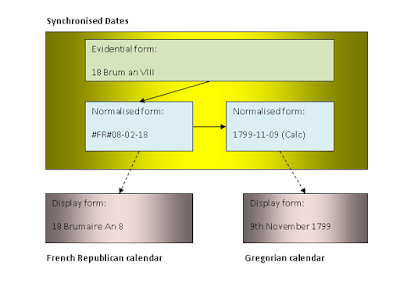

STEMMA therefore defines the notion of synchronised dates, where a single entity describes an item from a

written or printed source that embraces representations of the same day

according to two or more calendars. To see this in action, let’s look at the

combined Julian-Gregorian date example from above:

Figure 2 - Synchronised Julian and Gregorian

dates.

We can immediately see that the one evidential form — that

obtained from the consulted source — yields two normalised forms: one according

to the Julian calendar and one to the Gregorian calendar. Any number of display

forms can be generated from these normalised forms, dependent upon the regional

settings and personal preferences of the end-user.

Anyone who hasn’t read my previous two articles on dates

might be wondering why we need to store two normalised values when one will do,

employing a conversion algorithm when necessary. However, note that not all

such dual dates have an obvious

interpretation. For instance, double

years were occasionally used for months other than January to March which

makes little sense, and so needs some considerable interpretation. These two

normalised forms provide a direct interpretation of the relevant parts of the

evidential form.

When other calendars are considered then the conversion to the

Gregorian calendar — necessary for date comparison and timelines — is not

always reliable. In these circumstances, the same entity can describe the

direct interpretation of the evidential form and the calculated version

of it. I’ll return to the French Republican calendar example from the

aforementioned article in order to demonstrate such a conversion:

Figure 3 - Synchronised French Republican and

calculated Gregorian dates.

In effect, the same synchronised-date entity is used to

represent both dual dates and cases

where a value in an alternative calendar has been calculated. In both

circumstances it binds the multiple derived forms (normalised and/or

calculated) to a single evidential form.

[1] David

Ewing Duncan, The Calendar (London:

Fourth Estate Ltd, 1998), pp.288–289.

[2] “Calendar

(New Style) Act 1750”, transcription, legislation.gov.uk

(http://www.legislation.gov.uk/apgb/Geo2/24/23

: accessed 4 Aug 2015), in introduction; delivered by The National Archives of

UK.

[3] University

of Nottingham , “Historical Year and the Civil Year”, UK Campus: Manuscripts and Special Collections (https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/datingdocuments/historicalandcivil.aspx

: accessed 3 Aug 2015).

[4] Mike

Spathaky, "Old Style and New Style Dates and the change to the Gregorian

Calendar: A summary for genealogists", GENUKI

(http://www.cree.name/genuki/dates.htm

: accessed 4 Aug 2015), under "The cause of ambiguities - 2. The Start of

the year".

[5] E. G.

Richards, Mapping Time: The Calendar and

its History (1998; reprint, Oxford University Press, 2005), p.252.

No comments:

Post a Comment