In this three-part article, I want to summarise the current

state of the STEMMA® research project. Changes on the Web site have been

deliberately infrequent of late to enable me to find the time to finish it, but

that closure is now in sight. This data-model specification was designed to

represent our “days of future passed”,[1] or

the future laying-down of our daily events — using less surreal syntax.

The changes in the latest version of the specification were

recently summarised at STEMMA

V4.0, but I want to take this extra time to put those changes, and the

overall philosophy of STEMMA, into a perspective that can be recognised by

genealogists and software designers alike.

The original goals of STEMMA were twofold: to develop a data

model that could represent what I was already doing in genealogy, and to

investigate innovations that were not constrained by legacy products or models.

Too often, research for the future is limited by the legacies of the past, but

I found that I was in an ideal situation to try new solutions, and to look at

software genealogy from a different perspective.

The development of the specification, and of associated

software, has involved several iterations as one would expect from cycles of

experimentation. However, as I became a better genealogist then my requirements

also changed, and that meant unpicking some parts in order to re-knit them

differently. Early incarnations were primarily conclusion-based, but as I tried

to link conclusions (including so-called “facts”) to their supporting evidence,

and ultimately to the information in the underlying sources, then I realised

that this was a huge field that needed considerable thought — not just a bunch

of citations and some data links.

I tried hard to accommodate the main approaches to genealogy

in the data model (e.g. family trees), in additional to my own much-broader

scope, and to some of the more prevalent software schemes — albeit with much

generalisation. I did wonder, several times, whether it was indeed possible to

have a single model encompassing all of:

- Family Trees and pedigrees.

- Event-based genealogy, where we look at the events in the lives of the persons, or other subjects.

- One-name and one-place studies.

- Handling of non-family and non-familial relationships.

- Generalised micro-history, including additional subjects such as places, animals, and groups.

- Looking at places as another hierarchical type of subject rather than simply a name, and using a similar approach for groups.

- Clear separation of conclusions from evidence, and from source material.

- Personae, including multi-tier ones.

- Source-based genealogy, where conclusions are built from source information, rather than simply tacking citations onto conclusions.

- My bottom-up non-goal-directed approach to assimilating sources, described as Source mining.

- Integration of stories, research, proof arguments and other forms of narrative.

- Representation of diplomatic transcriptions.

- International applicability.

- Extensibility of type systems using namespaces.

- Generalised approach to sources & citations that accommodates layers, analytical notes, and even attribution.

You may think that such an ambitious set of goals would

yield a hugely complex Frankenstein’s

monster of a model, but the more I worked on it, the more things would slot

into place. At a certain point, a design — any design — reaches a level of order

and elegance that compares favourably with its functionality and capabilities,

and I believe it’s about there.

Previous attempts to describe STEMMA haven’t gained much traction

and this is partly due to the prevailing notion that genealogical software

products merely maintain a database of discrete data items. For instance, QuickLesson

20: Research Reports for Research Success, on the Evidence Explained site, relegates software considerations (other

than using a word-processor) to the final step: “Step 4: Data entry?” on the

basis that you will want to “… cherry-pick individual bits of data and record

them in a spread sheet or other data-management software”. If you’re going to

read on then you will need to exorcise all such notions and familiarities for

this will be fundamentally different!

One of the foundational elements of the STEMMA design is

that there are multiple independent sets of linkages within the model. What

this means is that the various entities, such as Persons, Places, Events, etc.,

are linked in multiple ways, each according to some real-world rationale, and

these cooperate to deliver a very rich structure. For instance, the lineage of

a Person is a set of hierarchical linkages that is independent of any association

with Events, and that means that the same model can be applied to a tree-based

arboreal genealogy or an event-based history, or a combination of these. Also,

the endless ways in which these linkages can be visualised is not prescribed by

the data model; that’s the prerogative of the software product.

This concept was eventually used to provide another set of

linkages that connected conclusions to evidence, to information, and to

sources. All the right concepts were there in the earlier incarnations, but it

wasn’t until v4.0 that they were connected properly.[2]

On the surface of it, the direction in which the

specification has proceeded has widened the scope of a data model far beyond

what many genealogists and software vendors have considered, or would like to

have considered. Indeed, it was pointed out to me during discussions within FHISO that I have the luxury of not having to worry

about backwards compatibility. This is partly why I now wish to illustrate how

this one data model can be applied to each of the main genealogical approaches,

and implicitly to suggest that these approaches do not have to be exclusive of

each other; we need to avoid the little-endian

versus big-endian[3]

arguments and see that they all have merit.

STEMMA has two notional sub-models: conclusional[4] and informational,

and the following sections will make reference to them.

Arboreal (tree) genealogy is characterised by a focus on

biological lineage. This is often mirrored by an underpinning database schema

designed specifically to support a tree-based view of lineage, or of pedigree.

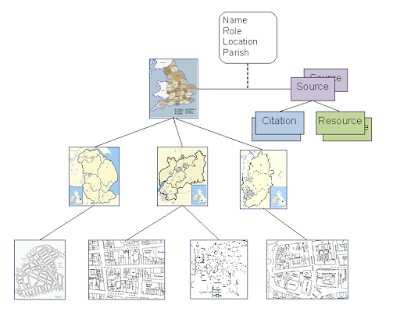

What the diagram below illustrates is that each Person entity

in a STEMMA tree can be associated with multiple Source entities, each

describing a specific source of information, and encapsulating the relevant

resources (such as images, documents, and artefacts) and citations.

Each of those sources can yield Properties — items of

extracted and summarised information — for the corresponding Person. For

instance, if a person was mentioned in multiple census sources then each of

them might yield a different residential address, differing ages (of course),

but even conflicting places of birth. Properties are one of two mechanisms for

associating information with a subject entity. The other (via the Source

entity) is part of the informational sub-model but Properties are part of the

conclusional sub-model. That is because they represent normalised information,

and any relationship or other subject identification involves a direct

connection to a conclusion subject entity, such as another Person. Each

Property basically consists of a name and one-or-more values (see Is That

a Fact?), and may be used to represent simple information, such as a name

or age, or a relationship to another subject, such as a Person or Place.

Although each Property can also retain a copy of the associated source

fragment, indicating how the information was originally expressed, the overall

mechanism is primarily designed for database-orientated products. They are

useful for presenting a synopsis of that subject, but they cannot be used for

detailed analysis or correlation.

As shown here, they are an ideal mechanism for arboreal

approaches where information is directly associated with the relevant Persons.

Although this linkage was designed to represent static Properties (ones that do

not change over time, such as a blood group), it could be used to represent

dynamic ones, such as a marriage date — but more on that later.

STEMMA V4.0 introduced the Animal entity as another subject

type, in addition to the existing Person, Place, and Group. Some might ask ‘why

animals’ but they are important to a great many people’s history. If anyone

ever writes about me in the (far-off) future, and fails to mention my dogs,

then I would haunt their hard-drive. Interestingly, it wasn’t difficult to

generalise the software support for Person entities to include Animal entities;

they both have biological lineage, and STEMMA’s name support already coped with

their differences.

The astute reader may be asking where marriages fit into

this arboreal scheme. It’s true that I mentioned handling a marriage date as a

static Property, but ideally they would be handled as Events (next section),

along with every other thing that happened in their lives. Not making it a

fundamental part of a tree actually made the inclusion of Animals easier since it

emphasised that marriage is not a prerequisite for lineage — trying to blend

the concepts together will fail, and quickly so!

One subtle but important point to note here: there is no “STEMMA

tree”, per se; a tree is just a way

of visualising the hierarchical linkages associated with lineage. All Person

entities may or may-not be linked in such a way, and that implicitly means that

a STEMMA Document (i.e. a file) can describe multiple independent trees.

Just as Persons and Animals share many characteristics, and

especially their lineage-based hierarchies, so too do Groups and Places; they

both have a type of hierarchy that is time-based. With lineage, every subject

has just two parent subjects — one male and one female — but with

organisational hierarchies, each subject has just one parent that may change

over time.

The following diagram illustrates how a place hierarchy has

a very similar relationship to sources and Properties in STEMMA.

Events are something that happened in a given place on a

particular date, or range of dates. Event-based genealogy gives a more dynamic

representation of information related to Persons, or other subjects, and so is

more applicable to family history

than to genealogy in its limited

literal sense (i.e. lineage).

Organising information both by geography and by time is an

essential step in the representation of history. The following diagram

illustrates a single Event that is supported by two sources. As above, the

associated Source entities can embrace multiple resources and citations. The

diagram shows that these sources may make reference to subjects of each of the

types supported by STEMMA: persons, animals, places, and groups; but they can

now yield dynamic Properties rather than the static ones mentioned above. That

is, each of the Property values can be traced to a particular time and place

via the Event entity and its supporting sources.

The Event entity is still part of the conclusional

sub-model, even though the Source entities encapsulate details of the

supporting sources. For instance, two mentions of a marriage date or place, say

from a certificate and from a newspaper announcement, may differ slightly, and

yet the Event entity would represent the conclusions about the true details.

Note, too, that each of the subject types in the above

diagram indicate that they are still part of their respective hierarchies. In

other words, the Event linkages are independent of the hierarchical linkages of

those subjects.

Unusually, STEMMA Events are also hierarchical. This means

that a complex event — one with structure that can be broken into separate

phases or layers — can be represented as a whole. A simple example of this

involves a voyage event whose embarkation and disembarkation occurred at

different times and places, and which can be represent as child events.

Narrative genealogy involves the use of humanly-generated

natural language to describe the persons, and other subjects, in our history,

as well as all the events that touched

them. In common with a number of other people, I strongly believe that software

cannot generate anything resembling readable narrative, and that advocates

demonstrate more misplaced pride than real-life use-cases.

Narrative can be used for essays, notes, reports, and many

other purposes, but STEMMA also includes transcriptions. This includes their structural and

presentational aspects such as paragraphing and line-counting, original

emphasis such as underlining or italics, corrections and other annotation, and

marginalia or footnotes. Since transcribed extracts will often appear in essays

or reports then narrative and transcription are both supported as a single

feature.

I will continue discussing this genealogical approach in

Part II of this series.

Source-based genealogy involves a focus on the source, and

the assimilation of the information therein. For instance, working with a

simple birth certificate might yield the names of the child and parents,

mother’s maiden name, father’s occupation, birth sex, the date and place of

birth, name and residence of the informant, and the date of registration.

Beginning from the source means that we can organise our copies of the

information (usually images and transcripts), create a source citation, and

have all of that information available before

we start any detailed analysis.

Conversely, and with online genealogy especially, the norm

is to cherry-pick selected names that have been extracted and entered into some

index for the user’s benefit. This divorces those names from any context

associated with the source, and so is insufficient for a detailed analysis.

Unfortunately, the underlying source is too-often ignored leaving users working with only partial information. It also means that citations are

generally an afterthought.

I will continue discussing this genealogical approach in

Part III of this series.

I want to round-off the first part of this series of

blog-posts by making some observations about genealogical software.

There are two broad approaches to any software design: the

first involves designing the code to provide specific product functionality,

usually as dictated by some product manager. The second involves taking a

step-back and designing for the bigger picture. This usually involves a

software architect and results in a more adaptable design with greater

potential for evolution. A case where the former has happened in genealogy is

where products were designed to support trees, and hence the biological lineage

of persons. Notwithstanding that lineage is not a true tree, those designs then found it hard to represent history,

evidence & sources, geography, reports & essays, or anything other than

persons (see The

Lineage Trap).

A User Interface (UI) is a crucial part of a software

product, not just because it can make a product easier or harder to use, but

because a well-designed UI can give a sense of the physicality of the data

being manipulated. When the computer world introduced Graphical User Interfaces

(GUI) then it became possible to depict things using pictures rather than text,

but also to give graphical control to the end-user. That meant the ability to

do such things as drag-and-drop or manipulate parts of a picture. A simple

example might be to indicate a data relationship by drawing a line between two

entities on the screen, as opposed to filling in a textual field.

Unfortunately, genealogical products tend to use a lot of form-fill, and

present a bunch of boxes rather than a tangible UI. Part of the reason for this

may be that such UIs are harder to create for the world of the Web, and harder

to use on hand-held devices. A consequence, though, is that those products

largely solicit conclusions. When asked to provide details of a spouse, say, an

end-user is typically invited to provide name, date-of-birth, etc., without

having to say where the information came from. At best, the user can tack on

some citation, or electronic bookmark.

Although STEMMA was initially conceived as supporting

import/export or long-term storage of data, that quickly became a secondary

feature. A result of its deep level of representation meant that no

database-orientated product could index it adequately to achieve its full

potential. However, indexing it into memory, on-the-fly, meant that (a) full and

efficient indexing was possible, (b) that no import/export was necessary as the

definitive source format could be exchanged, and (c) that no special

consideration was needed for long-term storage or backup of database content.

The article Do

Genealogists Really Need a Database? explained how reliance on a

conventional database is folly, and that it introduces performance degradation,

risk of corruption, incompatibility between different database vendors or

proprietary schemas, and forces the need to invent other representations for

import/export, etc.

[1] No, not the X-Men film title, which uses

“past” rather than “passed”; I am from a different generation. The title

borrows heavily from the 1967 concept album called Days of Future

Passed by the English rock group: The Moody Blues, of

whom I was, and still am, a huge fan.

[2] In the words of

British comedians Morecambe

& Wise, I wasn’t “playing all the wrong

notes", I was “playing all the right notes — but not

necessarily in the right order”.

[3] This terminology comes from the satirical novel Gulliver's Travels by Irish writer and

clergyman Jonathan Swift, in which two religious sects of Lilliputians are

divided between those who crack open their soft-boiled eggs from the little

end, and those who crack from the big end.

[4] The word conclusional is

not in most English dictionaries. The usage here ("of or pertaining to a

conclusion") may be found in: Bryan A. Garner, Garner on Language and Writing: Selected Essays and Speeches

(American Bar Association, 2009), p.330, where it compares the use of: conclusory, conclusional, and conclusionary.