- Ancestry.com (May 2012)

- RootsMagic (July 2012)

- WikiTree (August 2012)

- ourFamily•ology (September 2012)

- Calico Pie — UK (September 2012)

- Coret Genealogie — Netherlands (October 2012)

- Federation of Genealogical Societies (FGS) (October 2012)

- Federation of Family History Societies (FFHS) — UK (December 2012)

- brightsolid (owner of findmypast) — UK (December 2012)

- Mocavo (January 2013)

- Eneclann — Ireland (May 2013)

Wednesday, 15 November 2017

Thither FHISO

Monday, 2 October 2017

More on SVG Family Trees

Following my previous post on Interactive Trees in Blogs Using SVG, a number of people have signed-up to try the free utility for designing and generating their SVG trees.

These people have explored the possibilities and made valuable suggestions, including some with developer experience, and including one person running it under the WINE compatibility layer on a Mac (it was designed to run under Windows).

With the release of v3.0, the utility became a proper product rather than just a POC, and a number of enhancements and fixes were applied during the sub-releases of v3.0. These culminated in thumbnail images being supported in the browser output, and by the Tree Designer’s Edit-Person form, in v3.2.0.

An installation kit, documentation, and samples were placed in a Dropbox folder from where they can be downloaded by people who sign-up (either by contacting me via email, or from the right-hand panel of my blog).

The main purpose of this post is to announce the release of v4.0 of the utility, and to demonstrate a couple of the new features. The following is a summary of the new features, in roughly chronological order:

- Implemented 'id=' attributes on person-boxes so that they can be referenced by URLs and scrolled into view. This allows narrative text to reference specific person boxes in an SVG tree.

- Support for images and captions together in the Tree Designer person boxes, as per the browser output.

- Implemented multiple-selection of persons via Ctrl+Click operations. Affects interpretation of Copy-Person and Delete-Person operations.

- Implemented menu options to copy and paste persons or families (e.g. between different sessions).

- Include optional pan-zoom support for browser from external source. This allows the contents of specific SVG images to be panned and zooomed (see user guide).

- Changed border and text of empty boxes to faint grey to avoid them being too obtrusive.

- The Tree Designer’s window size and position are now saved and restored. It is no longer always maximized.

- Implemented zoom control in Tree Designer via menu options, and Ctrl/+ or Ctrl/- keystrokes (very similar to Web browsers).

- Added simple HTML toolbar to help with editing person and family notes.

- Implemented a RootKey parameter to emphasise the direct-line of a particular person up through ancestral generations.

One of the features I especially want to present is the Pan-Zoom feature. This uses open-source Javascript code to allow a user to navigate around a specific SVG tree image. It eliminates the need for both clunky scrollbars and the standard browser zoom support, which affects the whole page.

The first example is a tree that includes both images and captions in each of the boxes. Tooltips are enabled if you let the mouse hover over a box or a family circle. The +/Reset/- control in the bottom-right corner shows that the Pan-Zoom code is active, and so you can navigate around the tree and magnify/shrink it. Also, clicking on a person box or family circle expands biographical details into a separate information panel (dismissed with a Ctrl+Click on a person box or family circle).

The second example shows a tree in the vertical orientation. This tree also incorporates the Pan-Zoom code and dynamic information panels.

Articles and mentions:

A Copyright Casualty — Part I

A Copyright Casualty — Part II

A Copyright Casualty — Part III

Articles and mentions:

A Copyright Casualty — Part III

Articles and mentions:

More of a Life Revealed

Articles and mentions:

More of a Life Revealed

Articles and mentions:

More of a Life Revealed

Articles and mentions:

A Life Revealed

More of a Life Revealed

Articles and mentions:

More of a Life Revealed

Articles and mentions:

More of a Life Revealed

Notice that the panel for Mary Ashbee includes links to blog articles that mention her, as well as an image of her. Because such content is HTML-based then it can also include footnotes, tables, document scans, and more.

A larger example of Pan-Zoom that also incorporates the new direct-line RootKey feature may be found at Fieg & Sheehan Family, courtesy of Robert Fieg.

The tool to generate these trees is now freely shared with the genealogy blogging community. Since the time of writing, it has undergone many improvements, including thumbnail images and searchable photos. See SVG-FTG Summary.

Saturday, 15 July 2017

More on Margaret Hallam, née Astling

|

Date

|

Groom

|

Database

|

|

1725

|

Jacob Asling

|

"England Marriages,

1538–1973", FamilySearch

|

|

6 Feb 1726

|

Jacob Asling

|

Nottinghamshire Family

History Society (NottsFHS), Parish

Register Marriage Index, CD-ROM, database (Nottingham, 1 Jan 2013),

database version 3.0; CD hereinafter cited as NottsFHS-Marriages.

|

|

6 Feb 1725/6

|

Jacob Asling

|

FreeReg

|

|

1725

|

Jacob Asling

|

“England Marriages

1538-1973”, Findmypast

|

|

6 Feb 1725

|

Jacob Holing

|

“Nottinghamshire Marriages

Index 1528-1929”, Bishops’ Transcripts, Findmypast

|

|

6 Feb 1726

|

Jacob Asling

|

“Nottinghamshire Marriages

Index 1528-1929”, Findmypast

|

|

1725

|

James Ashling

|

“England, Boyd's Marriage

Indexes, 1538-1850”, Archdeaconry Marriage Licences, Findmypast

|

|

6 Feb 1725-6

|

James Ashling

|

“Nottinghamshire, England,

Extracted Church of England Parish Records”, Abstracts of Marriage Licences, Ancestry

|

|

6 Feb 1725

|

Jacob Asling

|

“England & Wales

Marriages, 1538-1988”, Ancestry

|

|

1725

|

Jacob Asling

|

“England, Select Marriages,

1538–1973”, Ancestry

|

|

Date

|

Groom

|

Bride

|

Parish

|

|

15 Jun 1735

|

James ASLING

|

Elizabeth WILLSON

|

Coddington all Saints

|

|

19 Aug 1751

|

James ASLING

|

Mary FRANDELL

|

Newark St Mary Magdalene

|

|

27 Jul 1756

|

Edward ASLING

|

Mary BOWMAN

|

Coddington all Saints

|

|

18 Mar 1775

|

James ASHLING

|

Elizabeth TAYLOR

|

Coddington all Saints

|

|

22 Jul 1784

|

James ASLING

|

Elizabeth BAKER

|

Coddington all Saints

|

|

3 Jul 1787

|

John ASLIN

|

Elizabeth WHAITE

|

Barnby-in-the-Willow All

Saints

|

|

24 Dec 1798

|

James ASLING

|

Elizabeth WATSON

|

Coddington all Saints

|

|

Date

|

Name

|

Age

|

Register Notes

|

|

1 Aug 1726

|

James ASLIN

|

-

|

Son of James

|

|

1 May 1735

|

Mary ASLING

|

-

|

|

|

18 Dec 1735

|

John ASLING

|

-

|

Son of James

|

|

2 Jan 1756

|

James ASLING

|

-

|

|

|

28 Dec 1769

|

Thomas ASSLEN

|

-

|

Son of James & Mary

|

|

26 May 1772

|

Mary ASLEN

|

-

|

Wife of James

|

|

1 Feb 1783

|

Elizabeth ASLING

|

52

|

Wife of James. Distemper

fever. [Calc. birth year 1731]

|

|

10 Oct 1789

|

James ASTLING

|

-

|

P.P. [possibly “parish

priest”, which is more Catholic, or per procurationem: “on behalf of”]

|

|

17 Jul 1798

|

Elizabeth ASTLING

|

40

|

Wife of James. Of a

lingering consumption. [Calc. birth year 1758]

|

|

9 Jul 1815

|

James ASLING

|

60

|

[Calc. birth year 1755]

|

|

11 Nov 1824

|

Elizabeth ASLIN

|

80

|

[Calc. birth year 1744]

|

|

Date

|

Given name

|

Father

|

Mother

|

Notes

|

|

17 Sep 1727

|

James

|

James ASLIN

|

Mary

|

Comprises one generation of

1727–1735.

|

|

19 Jul 1730

|

Edward

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

|

|

10 Sep 1732

|

Mary

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

|

|

13 Apr 1735

|

John

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

|

|

26 Aug 1753

|

Mary

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

Comprises a second

generation, following an 18-year gap, of 1753–1770.

|

|

5 Feb 1755

|

James [a]

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

|

|

14 Nov 1756

|

John

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

|

|

1 Oct 1758

|

Edward

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

|

|

2 Mar 1760

|

Joseph

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

|

|

25 Apr 1762

|

Sharlot

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

|

|

11 Sep 1763

|

Sarah

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

|

|

24 Mar 1765

|

David

|

James ASLING

|

Mary

|

|

|

1 May 1768

|

Thomas

|

James ASHLIN

|

Mary

|

|

|

29 Apr 1770

|

Martha

|

Jamas ASLEN

|

Mary

|

|

|

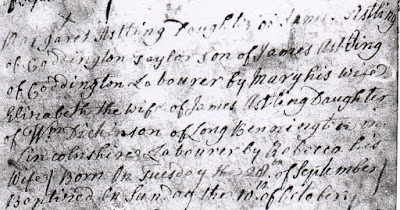

10 Oct 1784

|

Margaret

|

James ASTLING

|

Elizabeth

|

Born 28 Sep 1784. Father’s occupation “taylor”.

|

|

Name

|

Lifespan

|

Ref.

|

Context

|

Correlation

|

|

Mary

|

||||

|

Hall

|

(< c1705)–(> 1726)

|

Phillimore

|

m. James Ashling

|

Mary Hall married James

Ashling1 in Averham, and

had 5 children (4 baptised).She died in 1735, the same year as her infant son

(John).

|

|

Asling

|

(< c1706)–(> 1735)

|

Table 4

|

Baptisms of 4 children

|

|

|

Asling

|

?–May 1735

|

Table 3

|

Burial

|

|

|

Frandell

|

(< c1730)–(> 1751)

|

Phillimore

|

m. James Asling

|

Mary married James2 in 1751. After baptising

10 children, she died in 1772, just a couple of years after her last child

(Martha).

|

|

Asling

|

(< c1732)–(> 1770)

|

Table 4

|

Baptisms of 10 children

|

|

|

Aslen

|

?–May 1772

|

Table 3

|

Burial. “Wife of James”

|

|

|

Bowman

|

c1731–(> 1756)

|

Phillimore

|

m. Edward Asling

|

|

|

|

||||

|

James

|

||||

|

Ashling

|

(< c1705)–(> 1727)

|

Phillimore

|

m. Mary Hall

|

James1 married Mary in 1726, but she died in 1735 after 5

children. James1

remarried to Elizabeth Willson in the same year.

|

|

Asling

|

(< c1714)–(> 1735)

|

Phillimore

|

m. Elizabeth Willson

|

|

|

Aslin

|

?–Aug 1726

|

Table 3

|

Burial. “Son of James”

|

First son of James and Mary

Hall

|

|

Aslin

|

Sep 1727–?

|

Table 4

|

Baptised son of James &

Mary

|

Second son of James and

Mary Hall

|

|

Asling

|

(< c1730)–(> 1751)

|

Phillimore

|

m. Mary Frandell

|

James2 was born 1727, married Mary in 1751, Elizabeth

Taylor in 1775, and Elizabeth (Dickinson) Baker in 1784.

|

|

Ashling (w.)

|

c1728–(> 1775)

|

Phillimore

|

m. Elizabeth Taylor

|

|

|

Asling (w.)

|

c1729–(> 1784)

|

Phillimore

|

m. Elizabeth Baker

|

|

|

Asling

|

?–Jan 1756

|

Table 3

|

Burial

|

James1.

|

|

Astling

|

?–Oct 1789

|

Table 3

|

Burial

|

James2.

|

|

Asling

|

c1755–Jul 1815

|

Table 3

|

Burial

|

James3, son of James2

and Mary Frandell. Elizabeth Watson was his second wife, his first

(also Elizabeth) having died earlier the same year.

|

|

Asling

|

Feb 1755–?

|

Table 4

|

Baptised son of James &

Mary

|

|

|

Asling (w.)

|

c1758–(> 1798)

|

Phillimore

|

m. Elizabeth Watson

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Elizabeth

|

||||

|

Willson

|

(< c1714)–(> 1735)

|

Phillimore

|

m. James Asling

|

Of the same generation as

Mary Hall, who died in 1735, and so must be the second wife of James1.

|

|

Dickinson

|

c1743–(> 1766)

|

Phillimore

|

m. Thomas Baker

|

Elizabeth Dickinson married

Thomas Baker, and then James Asling2.

She gave birth to just one child: Margaret Astling. She died aged 80.

|

|

Baker

|

c1744–(> 1784)

|

Phillimore

|

m. James Asling (w.)

|

|

|

Aslin

|

c1744–Nov 1824

|

Table 3

|

Burial

|

|

|

Whaite

|

(< c1766)–(> 1787)

|

Phillimore

|

m. John Aslin

|

|

|

Taylor

|

c1732–(> 1775)

|

Phillimore

|

m. James Ashling (w.)

|

Second wife of James2.

|

|

Asling

|

c1731–Feb 1783

|

Table 3

|

Burial. “Wife of James”

|

|

|

Watson

|

c1772-(> 1798)

|

Phillimore

|

m. James Asling (w.)

|

James3 married an unidentified Elizabeth but she died in

1798. He then married a much younger Elizabeth Watson the same year.

|

|

Astling

|

c1758–Jul 1798

|

Table 3

|

Burial. “Wife of James”

|

|