My previous article briefly focused on George

Hearson, one of the three men hanged in 1832 for allegedly taking part in the

Nottingham riots following the rejection of the Reform Bill by the House of

Lords. At the time, I found no conclusive evidence for his parentage, but I

hate loose ends so I’ve examined more evidence and want to make a good case for

who they were.

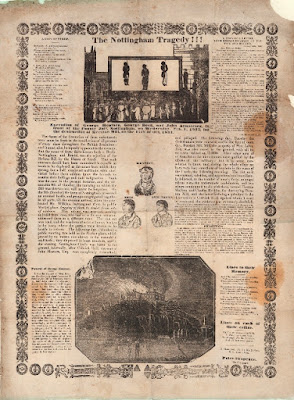

Figure 1 – Depiction of the hanging on 1 Feb 1832 as

appearing in a handbill.[1]

Online Trees

I had criticised the few online trees where I had seen

George Hearson because they were un-sourced, and because the details looked

suspect.

They declared George’s parents to be Thomas Hearson and

Francis [sic] King, and their

children to be:

William, 1792/3 (Southwell) –

Mary, 1797 (Arnold) –

Jane, 9 Nov 1802 (Arnold) –

Margaret, Jul 1804 (Arnold) –

Sara [sic], Sep 1807 (Arnold) –

George, 1810 – 1 Feb 1832

(Nottingham)

Francis [sic], Mar 1812 (Radford) –

John, 12 Aug 1814 (Radford) –

1880 (Nottingham)

The problems here include:

- The use of baptism dates as birth dates

- The use of baptism parish names as a places of birth

- Southwell was an outlier, which I will show to be incorrect

- There were more children after John

- There was no Thomas, a name much quoted in my evidence

Let’s start by assuming that Thomas Hearson and Frances King

really were George’s parents. They were married on 12 May 1793 at Arnold St.

Mary.[2]

Following the children in the parish records should give a map and timeline for

the family’s movements, but we have to consider possible name variations, and

this was the main reason for the existing trees being incorrect. Frances is sometimes (incorrectly)

written as the male Francis, and was

often abbreviated at that time to the diminutive Fanny. Thomas may have

been abbreviated to Thos. or Tho. (with or without the trailing

period), or even to Tom.

The trick to finding all the alternative combinations in a

clean sweep is to use wildcards, which in the case of the NottsFHS databases

are executed painfully slowly due to software design issues. The following

baptisms can all be linked to this couple:

|

Baptism

|

Given name

|

Parents

|

Occupation

|

Abode

|

Parish

|

|

9 Feb 1794

|

Thomas

|

Thos.& Fanny

|

|

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

28 Sep 1795

|

William

|

Thomas & Fanny

|

|

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

12 Nov 1797

|

Mary

|

Thomas & Frances

|

|

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

13 Jul 1800

|

Thomas

|

Thomas & Frances

|

|

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

9 Nov 1802

|

Jane

|

Thos. & Frances

|

|

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

26 Jul 1804

|

Margaret

|

Thos. & Frances

|

|

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

21 Aug 1806

|

John

|

Thos. & Frances

|

|

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

1 Sep 1807

|

Sarah

|

Thos. & Frances

|

|

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

1 Mar 1812

|

Frances

|

Thomas & Frances

|

|

|

Radford St Peter

|

|

28 Apr 1816

|

Jane

|

Thomas & Fanny

|

FWK

|

Radford

|

Radford St Peter

|

|

15 Aug 1819

|

Henry

|

Thomas & Frances

|

FWK

|

Radford

|

Radford St Peter

|

|

14 May 1821

|

Mary Ann

|

Thomas & Frances

|

FWK

|

Parliament St

|

Nottingham St Mary

|

Table 1 – Bapisms for children of

Thomas and Frances Hearson.[3]

So how do we know these are for the same couple? Well, there is continuity with the date of the wedding,

with the parish of the wedding, with the sequencing of the baptisms, with a geographical progression

from Arnold to the Nottingham town centre, and with the end of Frances’s child-bearing years. Also, where

there is an occupation, it is a consistent one; FWK is a Frame Work Knitter. Note that this occupation

is also consistent with the hosiery occupations mentioned in the previous article.

Note that we now have an entry consistent with what we know

of George’s brother, Thomas, but still no George.

Another thing to note is that the name of the last child

(Mary Ann) was also used by George and Charlotte for their short-lived and only

daughter, and by Thomas and Harriet for their daughter — not proof, but

indirect evidence.

The next step is to look at each of those parishes for

children who died prematurely. These are typically harder to identify since

fewer details are available for the correlation.

|

Burial

|

Given name

|

Abode

|

Notes

|

|

20 Jan 1799

|

Thomas

|

Arnold

|

Son of Thomas & Fanny

|

|

12 Feb 1805

|

Jane

|

Arnold

|

Dau of Thos. & Frances

|

|

31 Aug 1806

|

John

|

Arnold

|

Son of Thos. & Frances

|

|

15 Mar 1809

|

William

|

Arnold

|

Son of Tho. & Frances

|

Table 2 – Thomas/Frances Hearson

burials in Arnold St. Mary.[4]

This parish had annotated the relevant entries which made

them much easier to confirm.

|

Burial

|

Given name

|

Abode

|

Notes

|

|

14 Feb 1820

|

Henry

|

Radford

|

Aged 9 months

|

Table 3 – Thomas/Frances Hearson

burials in Radford St. Peter.[5]

|

Burial

|

Given name

|

Abode

|

Notes

|

|

19 Oct 1819

|

Mary

|

Radford

|

Aged 23

|

|

14 Jan 1824

|

Mary Ann

|

Stone Court [off parliament St]

|

Aged 2

|

|

10 Apr 1836

|

Thomas

|

Charlotte St

|

Aged 36

|

Table 4 – Thomas/Frances Hearson

burials in Nottingham St. Mary.[6]

There is no doubt that this is one family, with the

exception of the final Thomas entry

(George’s brother), but without an entry for George (or some reason why one is

not present) then we haven’t shown that it’s George’s family.

Note that Stone Court was between Dove Yard and Stanley’s

Passage, on the north side of Parliament Street, only 250 yards to the west of

Mount East Street. Hence, there’s a connection between this family and both of

the brothers George and Thomas through their geographical proximity.

If we combine these baptisms and burials, and match-up the

respective entries, then we can see that there was a high degree of mortality

in the family.

|

Given name

|

Baptism

|

Burial

|

||

|

Thomas

|

9 Feb 1794

|

Arnold St Mary

|

20 Jan 1799

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

William

|

28 Sep 1795

|

Arnold St Mary

|

15 Mar 1809

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

Mary

|

12 Nov 1797

|

Arnold St Mary

|

19 Oct 1819

|

Nottingham St Mary

|

|

Thomas

|

13 Jul 1800

|

Arnold St Mary

|

10 Apr 1836

|

Nottingham St Mary

|

|

Jane

|

9 Nov 1802

|

Arnold St Mary

|

12 Feb 1805

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

Margaret

|

26 Jul 1804

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

|

|

John

|

21 Aug 1806

|

Arnold St Mary

|

31 Aug 1806

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

Sarah

|

1 Sep 1807

|

Arnold St Mary

|

|

|

|

George

|

[c1809]

|

|

6 Feb 1832

|

Nottingham St Mary

|

|

Frances

|

1 Mar 1812

|

Radford St Peter

|

|

|

|

Jane

|

28 Apr 1816

|

Radford St Peter

|

|

|

|

Henry

|

15 Aug 1819

|

Radford St Peter

|

14 Feb 1820

|

Radford St Peter

|

|

Mary Ann

|

14 May 1821

|

Nottingham St Mary

|

4 Jan 1824

|

Nottingham St Mary

|

Table 5 – Combined baptisms and

burials for children of Thomas/Frances Hearson.

Note that William was not born in Southwell (as suggested in

online trees), and he was not born before his parents’ marriage. He was

baptised in the Arnold St. Mary parish, died aged 14, and was buried in the

same parish. This may upset the owners of those trees as it probably means that

they’re not related to George Hearson at all.

We can see that only four children are unaccounted for:

Margaret, Sarah, Frances, and Jane — all daughters. Also, although we have no

entry for George, his estimated date of birth/baptism fits perfectly into the

sequence.

Margaret married John Metheringham on 12 Oct 1822 at

Nottingham St. Mary,[7] and this

is confirmed by her details in the 1851 census at 29 Pipe St, Southwell Rd.[8]

Frances married Charles Wilkinson on 15 Nov 1830 at Nottingham St. Mary,[9]

and this is also confirmed by her details in the 1851 census at Lomas Yd,

Bellar Gate.[10]

This leaves just Sarah and Jane, and so we might expect to

see them staying with their mother in the 1841 census. Well, they were there,

but under the surname “Earson” (Nottingham is renowned for dropping its

aitches).

|

Name

|

Sex

|

Age

|

Birth year

|

Occupation

|

Place of birth

|

|

Frances

|

F

|

65

|

1776

|

Wid[ow]

|

Nottinghamshire

|

|

Sarah

|

F

|

30

|

1811

|

|

Nottinghamshire

|

|

Jane

|

F

|

25

|

1816

|

|

Nottinghamshire

|

Table 6 – 1841, family of Frances

Hearson. Rice Place, off Barker Gate.[11]

Now we’re getting somewhere because Barker Gate was not only

the last resting place of George, but it was also the address of Thomas’s

daughter, Mary Ann, when she died in 1851. In fact, Rice Place was just over

the wall from George’s burial ground. This provides the link between Frances,

George, and the Thomas who was the brother of George.

We can now determine that Frances died aged 73, and was

buried on 5 Mar 1848 at Nottingham St. Mary,[12]

implying

that she was born c1775. A newspaper report gives the date of her death as 2

Mar 1848: “On the 2d instant, in Riste-place, Barker-gate, aged 73 years, Mrs.

Frances Hearson, widow".[13]

By coincidence, I had previously shown that Riste Place was a later name for

Rice Place.[14]

The 1841 census indicates that her husband, Thomas, had died

before then (i.e. before 6 Jun 1841). The previous article presented evidence

that George’s father died almost a year before his own death (i.e. in 1831).

The best candidate for this is the Thomas of Nottingham who died aged 65 and

was buried at Arnold St. Mary on 10 Apr 1831,[15]

implying that he was born c1766. This entry is almost certainly the right one

for the husband of Frances because he was living in Nottingham, and yet was

buried in Arnold (4 miles north of the town) where his family would have been

interred.

In the previous article, I had established that George’s

brother, Thomas, of Charlotte Street, had died aged 36, and was buried on 10

Apr 1836 at St. Mary. There was no obvious record of his widow’s burial in that

parish, or in any other, and so I wanted to establish why. I had only tracked

his widow, Harriet, to the 1851 census, but it wasn’t hard to find her in the

1861 census:

|

Name

|

Role

|

Status

|

Sex

|

Age

|

Birth year

|

Occupation

|

Place of birth

|

|

Harriett

|

Head

|

Widow

|

F

|

58

|

1803

|

Lace Mender

|

Lenton, Nottinghamshire

|

|

Harriett

|

Daughter

|

Single

|

F

|

37

|

1824

|

ditto

|

St Mary, Nottingham

|

Table 7 – 1861, family of Harriet

Hearson. 12 Birkin Terrace, off St. Ann’s Well Rd.[16]

There was a suggestion in the GRO index of civil

registrations that Harriet had died late in 1861, not long after the above

census. The reason why her burial was not in any parish registers was that she

was buried in Nottingham’s privately-run General Cemetery.

The following is a list of people interred in the same plot:

|

Name

|

Burial

|

Death

|

|

Annie Clarke

|

03 Jun 1915

|

Unrecorded

|

|

James A. Dicks

|

11 Jun 1913

|

Unrecorded

|

|

John Toone

|

20 Feb 1870

|

Unrecorded

|

|

Harriet Hearson

|

11 Nov 1861

|

08 Nov 1861

|

|

Frank Hearson

|

02 Jul 1861

|

29 Jun 1861

|

|

Ann Toone

|

25 Jan 1855

|

22 Jan 1855

|

Table 8 – Burial register details for

Harriet Hearson.[17]

This cemetery was very close to the parish of Lenton, where

Harriet was born. The Frank Hearson is currently unidentified, but note the

surname Toone. In the previous

article, I indicated that one of the sons of Thomas/Harriet, John Thomas

Hearson, married a Mary Ann Toone in 1849, thus suggesting a strong family connection

with this burial plot.

As a final note, I came across an 1829 report in the London

Gazette that Thomas’s work as a commission agent ran into trouble, and that he

became insolvent: “Thomas Hearson, formerly of Nile-Street, Bobbin and

Carriage-Maker, and Commission-Agent, and late George-Street, all in the Town

of Nottingham, Commission-Agent”.[18] In

1831, a few months before the riots, a partnership was also dissolved: “Sneath

William, Sneath Walter, and Hearson Thomas, Nottingham, twist net lace and thread

commission agents”.[19]

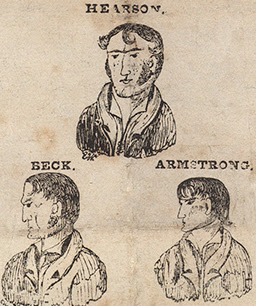

Figure 2 – Caricatures of the hanged men, as appearing in

a handbill from 1832.[20]

The Nottingham Castle Museum currently has a Riot

Gallery that exhibits details and artefacts associated with the 1831 riots

and the 1832 executions. One of these is a handbill

or pamphlet that was published shortly after the executions, selling for

twopence (two pence, pronounced tuppence),

and which included a copy of Hearson’s

final letter to his wife and mother. The handbill is undated but it is

likely that the newspaper versions of his letter were derivatives of this copy,

and that would place its publication before 10 Feb 1832. Both the museum and

Richard Gaunt — Associate Professor in the history department of Nottingham

University — have been kind enough to share images of this with me, and allow

me to present it in this article.

Figure 3 – Handbill detailing the executions, 1832.[21]

At the bottom of the image of the burning castle, there’s a

barely-legible inscription of “E. WILD, DEL. &SC. NOTTM”. E. Wild was a local

printer and a self-taught artist in wood engraving. The final letters are

associated with printmaking: “del.” meaning “drawn by” and “sc.” meaning “engraved

by”.

The previous article mentioned that George was involved in

bare-knuckle boxing using the name “Curley Hearson”, and a number of newspaper

reports were found that placed these bouts between 1828 and 1831.[22]

There are undeniable links that indicate George was the son

of Thomas and Frances Hearson, and no conflicting evidence, but what we do not

have is either a baptism or a burial record.

We know that the family moved from the parish of Arnold St.

Mary to Radford St. Peter between March 1809 and March 1812, and then to

Nottingham St. Mary around 1820; however, Radford St. Peter was demolished in

1811 and rebuilt in 1812.[23]

Although some events were still being recorded during that time, they might

have been just for existing parishioners. In other words, it may be that George

fell between the chairs as far as being

baptised.

Although Hearson was born in Nottingham, Beck was from

Wollaton, and Armstrong from Pleasely, near Mansfield. Beck’s funeral was

recorded on 2 Feb 1832 at Wollaton St. Leonard (in a coffin was provided by

Lord Middleton of Wollaton Hall[24]),

but no burial is recorded in a parish register for Hearson or Armstrong. Armstrong was

actually buried in the “old burial ground, Barker Gate” of St. Mary in the

afternoon of the execution,[25]

and we have already established that Hearson was buried in burial ground no. 2

of St. Mary on 6 Feb 1832. Does this mean that they were abandoned by their

parish?

A check of the original registers confirmed that there were

no misspellings, erasures, or missing entries (as when a page is torn out).

Not all of Hearson’s funeral requests, as expressed in his

letter, were complied with:

Funeral of George Hearson -- It

was the request of Geo. Hearson that his body should remain till Sunday, the

5th of February, namely, four days after his execution. It was also his request

it will be perceived by the letter in the upper column, that laurel should be

worn on the breasts of those who followed him, in addition to white ribbons.

This request could not be complied with, owing to the convulsed state of the

town, and the multitude which it was likely to congregate. The order of the

Sheriff, therefore, was that the body should not be interred on Sunday, but

must be consigned to its mother earth before 12 o'clock on Monday. This

peremptory order was complied with, and accordingly, at 25 minutes past 11, the

procession moved towards the burial-ground of St. Mary's Church, in

Barker-gate, where the remains of this unfortunate young man was interred, in

the presence of at least 15,000 spectators, who all deplored the cause of his

premature death. His followers and bearers were dressed most respectably, and

the solemn scene was one that will never be forgotten in Nottingham.[26]

Also, one of the funeral aspects that I previously reported

was later retracted by the newspaper:

We are requested to state that

"the choir of singers" belonging to the Wesleyan Methodists was not

present at Hearson's funeral, as erroneously stated in our last; -- and the

hymn sung on that occasion was without the concurrence of the Rev. R. Pilter,

who (with the Rev. T. Harris) left the ground immediately after he had closed

his address.[27]

Robert Pilter (born in Sunderland, 4 Jan 1784) and Thomas

Harris (born Morton-Corbet, Salop, 30 May 1791) were both preachers in the

Wesleyan Methodist Church. We can see that neither George nor his parents were

of this church given their Church-of-England parishes, and hence my previous

suggestion of this being cause for the missing records does not hold water.

The Wesleyan ministers were providing more comfort to all

the condemned men than their respective parish ministers:

After the condemnation of the

five unhappy men, several gentlemen of the Wesleyan Methodist persuasion were

assiduously kind, in endeavouring the impart religious instruction, and to

prepare them, so far as the aid of prayers and human agency can do, for the awful

change they were about to undergo.[28]

Although from 1752, the bodies of executed murderers were

not returned to their relatives for burial, and the government did not want their

bodies to have a full funeral or be buried in consecrated ground, for other

crimes (up to 1832) the body could be claimed by friends or relatives for

burial, which could then take place in consecrated ground. The Anatomy Act of

August 1832 (very close date) removed dissection

from the statute book, but it also directed that the bodies of all executed

criminals belonged to the Crown and were then to be buried in the prison

grounds in unmarked graves.[29]

My conclusion, therefore, is that the parish of St. Mary

deliberately failed to record the interment of both Armstrong and Hearson, despite

the huge public show of sympathy for them.

It is also my belief is that there was some government

influence in this matter. The government were insistent on having their

executions, no matter how weak or suspect the evidence, since they needed to

set an example; they needed a deterrent against any such rebellious acts in the

future.

UPDATE -- The marriage of Thomas Hearson was witnessed by Elizabeth and Thos Greenwood. The marriage of George Hearson was witnessed by John and Margaret Metheringham. This one is important because the article already establishes that Margaret was the sister of Thomas, and so substantiates the conclusion that George was part of that same family, i.e. the brother of both Thomas and Margaret.

UPDATE -- "E.Wild" was Ebenezer Wild, a local printer and a self-taught artist in wood engraving. He married Sarah Booth in 1829. They had a son (Henry Mansel) in 1842, and were living on Independent Hill in that July. In the August, they left and moved to 13 St. Martin's-le-Grand, London (Nottingham Review and General Advertiser for the Midland Counties).

UPDATE -- "E.Wild" was Ebenezer Wild, a local printer and a self-taught artist in wood engraving. He married Sarah Booth in 1829. They had a son (Henry Mansel) in 1842, and were living on Independent Hill in that July. In the August, they left and moved to 13 St. Martin's-le-Grand, London (Nottingham Review and General Advertiser for the Midland Counties).

[1] [Anonymous],

“The Nottingham Tragedy ! ! !”, handbill (Nottingham, 2 Park Row: J. Thompson,

printer, [1832]); Nottingham City

Museums and Galleries, accession no. NCM 1929-3; image displayed with their

courtesy; this image heavily-cropped but full image appearing below; alternative online digital image, Richard Gaunt, “Emotive Objects at Nottingham Castle: Part

3”, Nottingham University, A View from

the Arts, 2 Feb 2016 (http://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/arts/2016/02/02/emotive-objects-at-nottingham-castle

-3/

: accessed 18 Oct 2016); handbill hereinafter cited as Executions-handbill. Nottinghamshire Archives has an independent

original, ref. no. DD/1725/3, accession no. 4390.

[2]

Nottinghamshire Family History Society (NottsFHS), Parish Registers Marriage Index, CD-ROM, database (Nottingham, 1 Jan 2013), database version 3.0, entry for Thomas Hearson and

Francis King, using quoted details; CD hereinafter cited as NottsFHS-Marriages.

[3]

NottsFHS, Parish Registers Baptism

Transcriptions, CD-ROM, database (Nottingham, 1 Jan 2013), database version

6.0, entries for tho%s% he%son and f%an% between 1793 and 1825; CD hereinafter

cited as NottsFHS-Baptisms.

[4]

NottsFHS, Parish Registers Burial

Transcriptions, CD-ROM, database (Nottingham, 1 Jan 2013), database version

6.0, entries for Arnold St. Mary parish and quoted details; CD hereinafter

cited as NottsFHS-Burials.

[5] NottsFHS-Burials, entries for Radford

St. Peter parish and quoted details.

[6] NottsFHS-Burials, entries for Nottingham

St. Mary parish and quoted details.

[7] NottsFHS-Marriages, entry for quoted

details.

[8] "1851

England Census", database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com :

accessed 17 Oct 2016), household of John Metheringham (age 49); citing HO 107/2132,

folio 482, page 28; The National Archives of the UK (TNA).

[9] NottsFHS-Marriages, entry for quoted

details.

[10] "1851

England Census", database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com :

accessed 17 Oct 2016), household of Charles Wilkinson (age 38); citing HO 107/2131,

folio 370, page 17; TNA.

[11] "1841

England Census", database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com :

accessed 18 Oct 2016), household of Frances Earson [Hearson] (age 65), name

mis-transcribed as “Easton”; citing HO 107/869, book 2, folio 13, page 20; TNA.

[12] NottsFHS-Burials, entry for quoted

details.

[13] "Died",

Nottingham Review and General Advertiser

for the Midland Counties (10 Mar 1848): p.4, col.3; paper hereinafter cited

as Nottm-Review.

[14] Tony

Proctor, “Cemetery Road, Nottingham”, RootsWeb, NOTTSGEN-L Archives, 5 May 2013 (http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/NOTTSGEN/2013-05/1367749329

: accessed 18 Oct 2016).

[15] NottsFHS-Burials, entry for quoted

details.

[16] "1861

England Census", database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com :

accessed 18 Oct 2016), household of Harriett Hearson (age 58), name

mis-transcribed as “Heurson”; citing RG 9/2462, folio 63, page 35; TNA.

[17] “The

central database for UK burials and cremations”, database with images, deceased online (https://www.deceasedonline.com

: accessed 18 Oct 2016), entries for grave for Harriet Hearson, 1861,

Nottingham General Cemetery, grave ref: /11455.

[18] "The

Court for Relief of Insolvent Debtors: …appointed to be heard … at

the Court-House ... 9th day of October 1829 ...", London Gazette, issue 18612 (18 Sep 1829): p.1747.

[19] "Partnerships

Dissolved", Nottm-Review (22 Jul

1831): p.2, col.5; citing “from Tuesday's London

Gazette”.

[20] Executions-handbill; this image heavily-cropped but full

image appearing below.

[21] Executions-handbill; full image.

[22]

"The Fancy", Nottm-Review (19

Dec 1828): p.3, col.3 (bottom). "Nottingham Fancy", Bell's Life in London and Sporting

Chronicle (9 May 1830): p.3, col.2. "Nottingham Fancy", Bell's Life in London and Sporting

Chronicle (29 May 1831): p.3, col.2.

[23]

"Radford St. Peter: History", Southwell

& Nottingham Church History Project (http://southwellchurches.nottingham.ac.uk/radford-st-peter/hhistory.php

: accessed 19 Oct 2016).

[24] "EXECUTION

of Beck, Hearson, and Armstrong", Nottm-Review

(3 Feb 1832): p.3, col.7.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Executions-handbill, bottom-left panel.

[27] Nottm-Review (17 Feb 1832): p.3, col.4.

[28]

"EXECUTION of Beck, Hearson, and Armstrong", Nottm-Review (3 Feb 1832): p.3, col.5.

[29] “The

history of judicial hanging in Britain 1735 – 1964”, capitalpunishmentuk.org (http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/hanging1.html#after

: accessed 19 Oct 2016), under “Burial”.