Making transcriptions of records is not as common amongst

genealogists as you might expect, but why is that? What do we need in order to

create useful transcriptions? If we’re part of the minority who do make them

then where should we attach them?

Because of the availability of online data sources, and the

ease with which digital copies can be created (owner permitting of course),

many people believe they do not need full transcriptions of records. They might

claim that since they can visit an online image, or they have a digital scan in

their own data collection, then they can read it perfectly well without having

it typed out. Whether it’s a baptism entry, a newspaper report, or a census

page, many genealogists therefore find they have a growing collection of

equivalent JPEG files sitting on the periphery of their data.

What I mean by this is that such a file can be pointed to,

or referenced, by other data, but it cannot reference anything itself[1] or

be textually searched. This means the information is not truly integrated into

your data. The arguments for adding mark-up to a transcription in order to

achieve this are almost exactly the same ones that I made for using mark-up in authored

narrative at Semantic

Tagging of Historical Data. This allows, for instance, references to

people, places, events, dates, etc., in that transcription to be connected to

the relevant entities in your data.

A transcription requires more though. It also requires a way

of indicating transcription anomalies — parts that deviate from the normal flow

— such as marginalia, footnotes, interlinear/intralinear notes, struck-out

text, and uncertain characters or words. Both the uncertain characters and the

uncertain words may require annotation to provide suggestions and

possibilities, both of which must be honoured during searches. A transcription

also requires an indication of any original emphasis, such as italics or

underlining. NB: the original use of italics, underlining, footnotes, etc., in

something being transcribed is different to their deliberate use in a written

report, and so must use a distinct form of mark-up.

Traditional editorial notations for transcriptions are not

well-suited to digital text as they do not facilitate efficient and accurate

searching. TEI has comprehensive sets of

mark-up for handling transcription issues but falls short when applied to genealogical

data, and probably historical data in general. It is certain that some

specialised mark-up is required, but how you visualise a transcription on-screen

is a separate consideration. The same mark-up could alternatively show

multi-coloured and hyper-linked text, or the plain editorial notation. That

sort of flexibility only comes from using a computerised annotation rather than

human annotation.

The fact that both transcription and authored narrative may

co-exist in the same written report led to STEMMA® unifying them in its own

mark-up. Those distinct usages — for transcriptions and for generating new narrative

(e.g. essays, reports, inference, etc.) — have some similar and markedly

different characteristics as follows:

- Transcription (including transcribed extracts) — requires support for textual anomalies (uncertain characters, marginalia, footnotes, interlinear/intralinear notes), audio anomalies (noises, gestures, pauses), indications of alternative spellings/pronunciation/meanings, indications of different contributors, different styles or emphasis, and semantic mark-up for references to persons, places, groups, animals, events, and dates. The latter semantic mark-up also needs to clearly distinguish objective information (e.g. that a reference is to a person) from subjective information (e.g. a conclusion as to whom that person is).

- Narrative work — requires support for layout and presentation. Descriptive mark-up captures the content and structure in a way that provides visualisation software with the ultimate control over its rendering It needs to be able to generate references to known persons, places, and dates that result in a similar mark-up to that for transcriptions. The difference here is that a textual reference is being generated from the ID of a Person entity, say, as opposed to marking an existing textual reference and possibly linking it to a Person with a given ID. Also needs to be capable of generating reference-note citations and general discursive notes.

As you can imagine, in order to generate a quality

transcription, and to incorporate semantic links and annotation, a very good

software tool is needed. It would be something like a specialised

word-processor tool, but most of us are left using general-purpose

word-processor tools that have none of the required facilities. This will be a

secondary reason why so few transcriptions are made.

So where do I attach transcriptions in my own data? In order

to explain, I first need to convey something of the structure of my data.

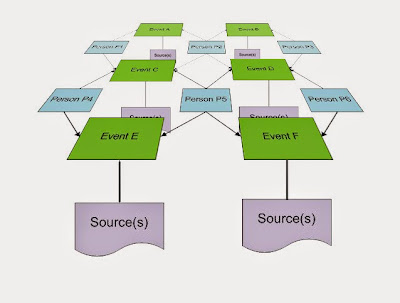

This simplified view of the rich connections in the STEMMA

tapestry doesn’t show its places, or groups, or lineage links between people,

or hierarchical/protracted events. That would be too complex! What it does show

is a network of multi-person events and the relationship of sources to those events.

Notice that the sources are attached to the events, and not to the people. As

already explained in Evidence

and where to Stick It, the vast majority of our evidence – if not all of it

– relates to events; things that happened in a particular place at a particular

time. In other words, our entire view of history rests on discrete and

disjointed pockets of evidence describing a finite set of events. Everything

else is inference and interpolation creating as smooth a picture as we can.

So what is the general form of these underlying source

entities in the data? Our real-life sources may be remote, such as a document

in an archive or a book in a library, or local, such as a family letter or a

photograph. In both cases, we may have a digital scan of the items. STEMMA[2]

has two important concepts that it employs for sources:

- Resource – This describes some item in your local data collection, including not just files on your disk, but also physical artefacts or ephemera.

- Citation – Despite the name, this is merely a link to some source of information. A traditional printed citation may be generated from it, but this software entity also incorporates collections, repositories, and even attribution; possibly chaining them together.

Either or both of these may apply,

therefore. A full transcription would be associated with the Resource entity that

would describe any physical or digital edition of the associated material. In

the case where you may have transcribed a document in an archive, or even from

one of the online content providers, the transcription should still be placed

in a Resource entity rather than a Citation entity, even though the latter is

possible.

Genealogist Janice Sellers, in her blog-post at Transcription

Mentioned on Television, explains how transcriptions of documents are

valuable for sharing the details with family and friends. She recounts how she

tried to convince a well-known British TV program to advise their guests to

make transcriptions of their historical documents and heirlooms.

STEMMA’s mark-up is primarily

about semantics. Shallow semantics would

mark an item as, say, a person reference but without forming a conclusion about

who the person was. Deep semantics

involve cross-linking references to persons, places, groups, events, and dates,

to the relevant entities in your data. I have previously tried to convey this using

the worked example of an old family letter at Structured

Narrative.

Genealogist Sue Adams has taken

the concept of semantic mark-up in transcriptions to a deeper level on her Family Folklore Blog.

Her worked examples clearly demonstrate the temporal nature of historical

semantics. Anyone with a passing interest in the Semantic Web and RDF is

encouraged to read about “temporal RDF” and consider why it doesn’t yet exist. You

may find a lot of theoretical work that considers things like temporal graphs but very few real

examples like hers. In an ideal world, the developers of such technology would

be working closely with the people who need to utilise it.

[1] I’m ignoring the

issue of meta-data held within an image until a future post. The issue here is

one of the text in an image making discrete references to its subjects rather

than anything to do with image cataloguing.

[2] STEMMA V2.2 — which includes

important refinements here — has

just been defined but, at the time of writing, I am still preparing to

painstakingly update the Web site. The landing page will indicate when this is

complete.

No comments:

Post a Comment